HOSTILITIES: ESTATES – UNIVERSITIES

1.

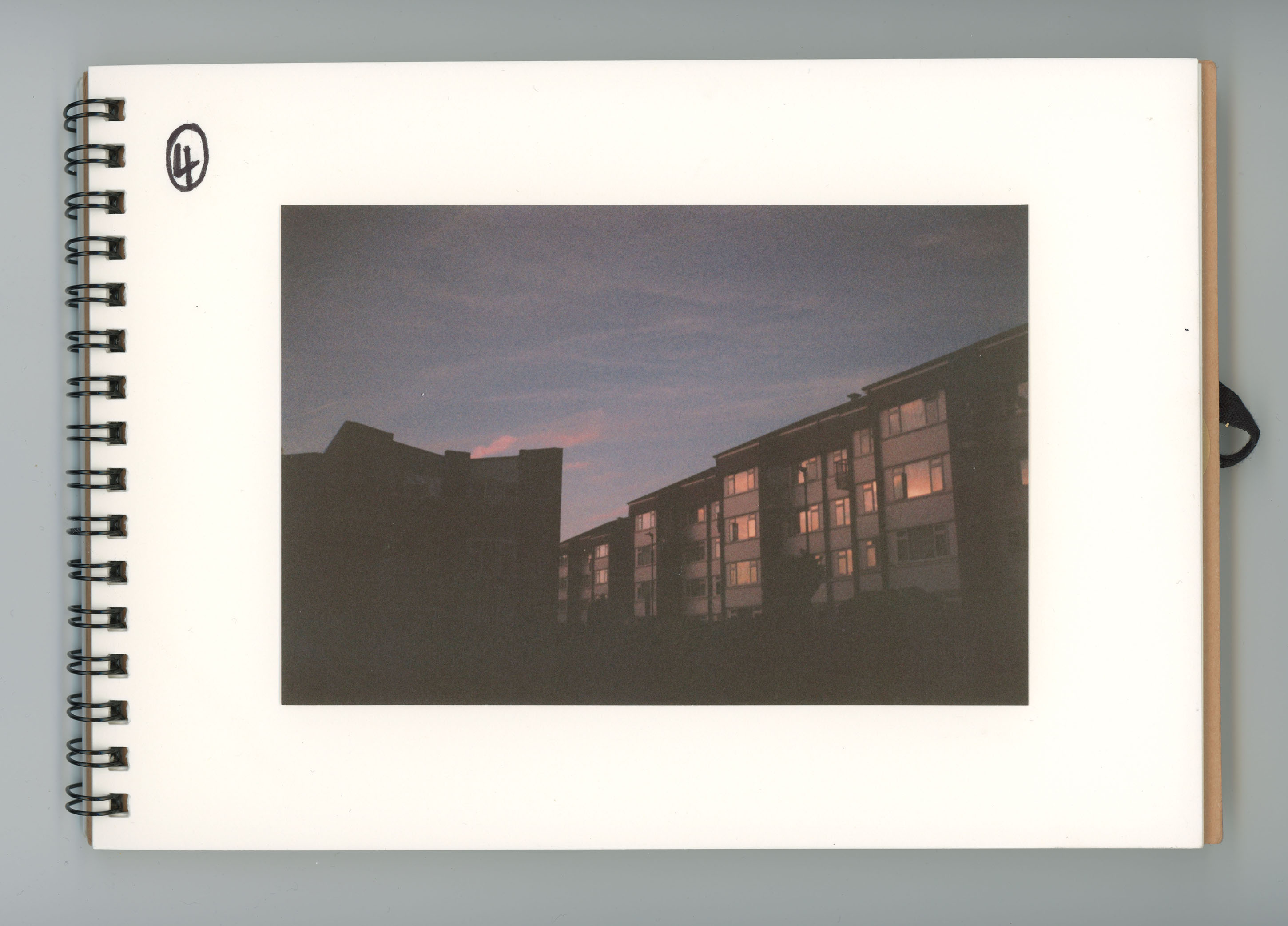

My understanding of the hostile environment is situated somewhere between council estates and their surrounding neighbourhoods, as well as universities and their surrounding institutions. I observe the pervasiveness of the hostile environment. It exists in mundane spaces politically, punitively and in policy. It is subsumed in hostilities of negligent authorities and negligent governments. And yet the beauty in the struggle, is that individuals and communities still find ways to thrive. Roses, fighting against dull grey concrete skies.

1.

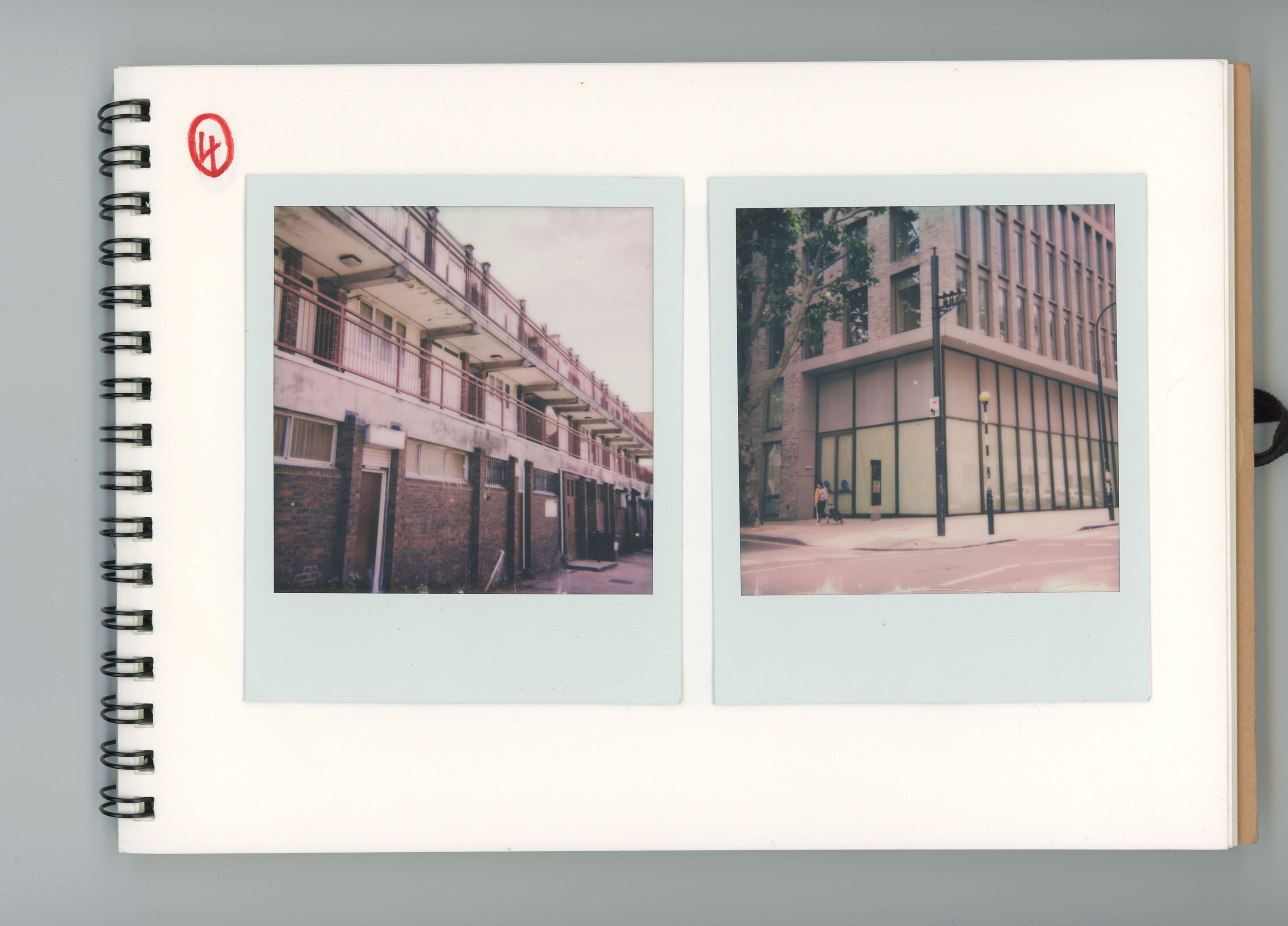

For the local resident any council estate is paradoxical. For as much as it is a place of joy, kids laughter in the air and summertime glee. It can also be a place of visceral hostility, deaths upon deaths. Panopticon helicopters flying overhead. Section 60s, dispersal orders and annual summertime violence.

In all honesty I hoped and prayed that COVID-19 would put the summertime shootings on hiatus. A week later those hopes are blindsided. A young man I’ve previously photographed is caught up in a shooting. Thank God he survives. Block parties are thrown and riot police storm into estates. Pleasant summertime dialogues are exchanged over garden fences. It’s just another day.

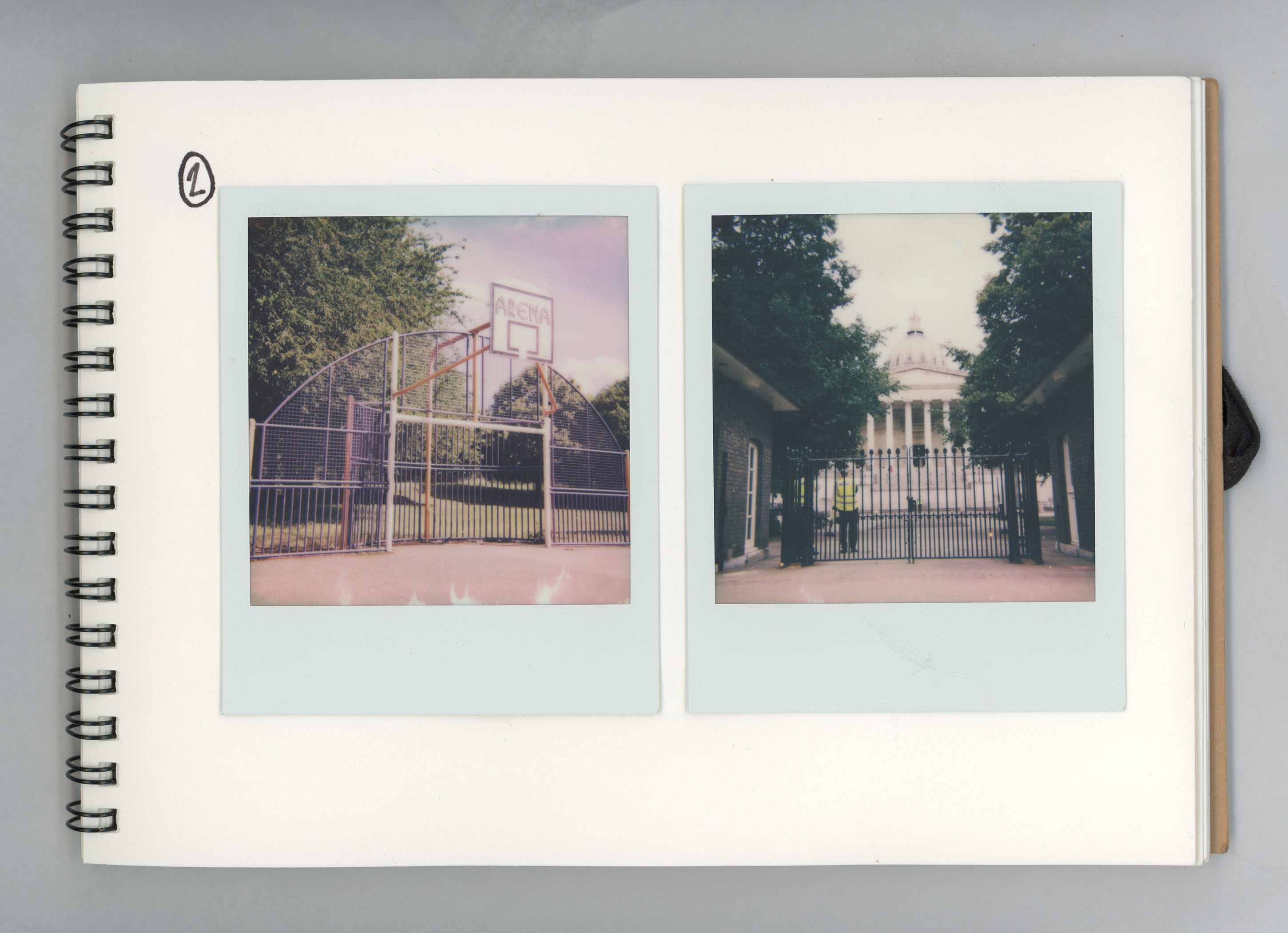

2.

Sometimes I get caught off guard. I can’t help but whole heartedly smile/grimace when visiting different council estates. Checking in on friends, family and my contemporaries. We’ve made homes and memories in the presence of hostile environments. We’ve experienced true Black joys and grieved painful Black deaths. Looking up onto different skies, and onto different days. Dare we hope for a different tomorrow?

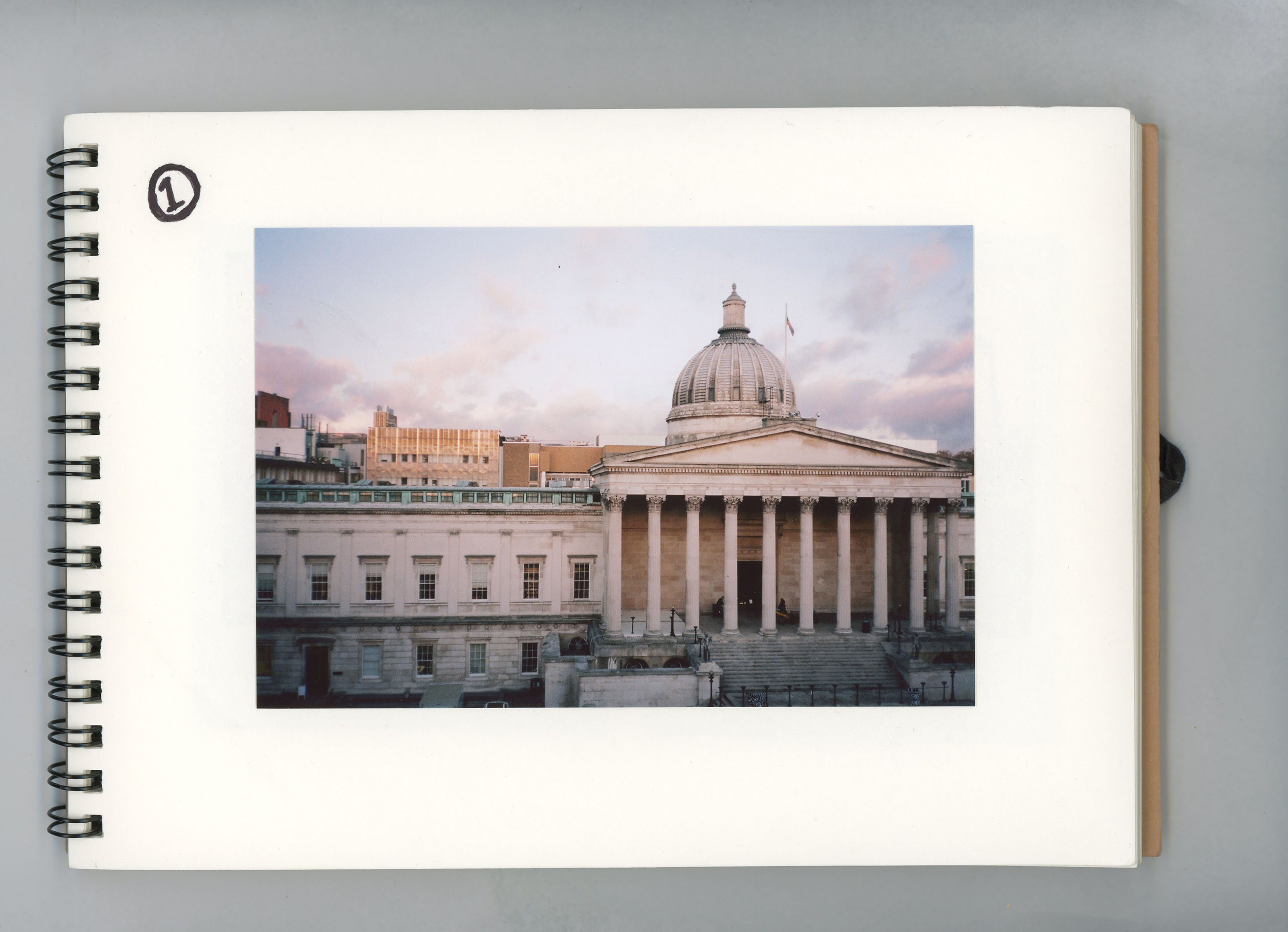

2.

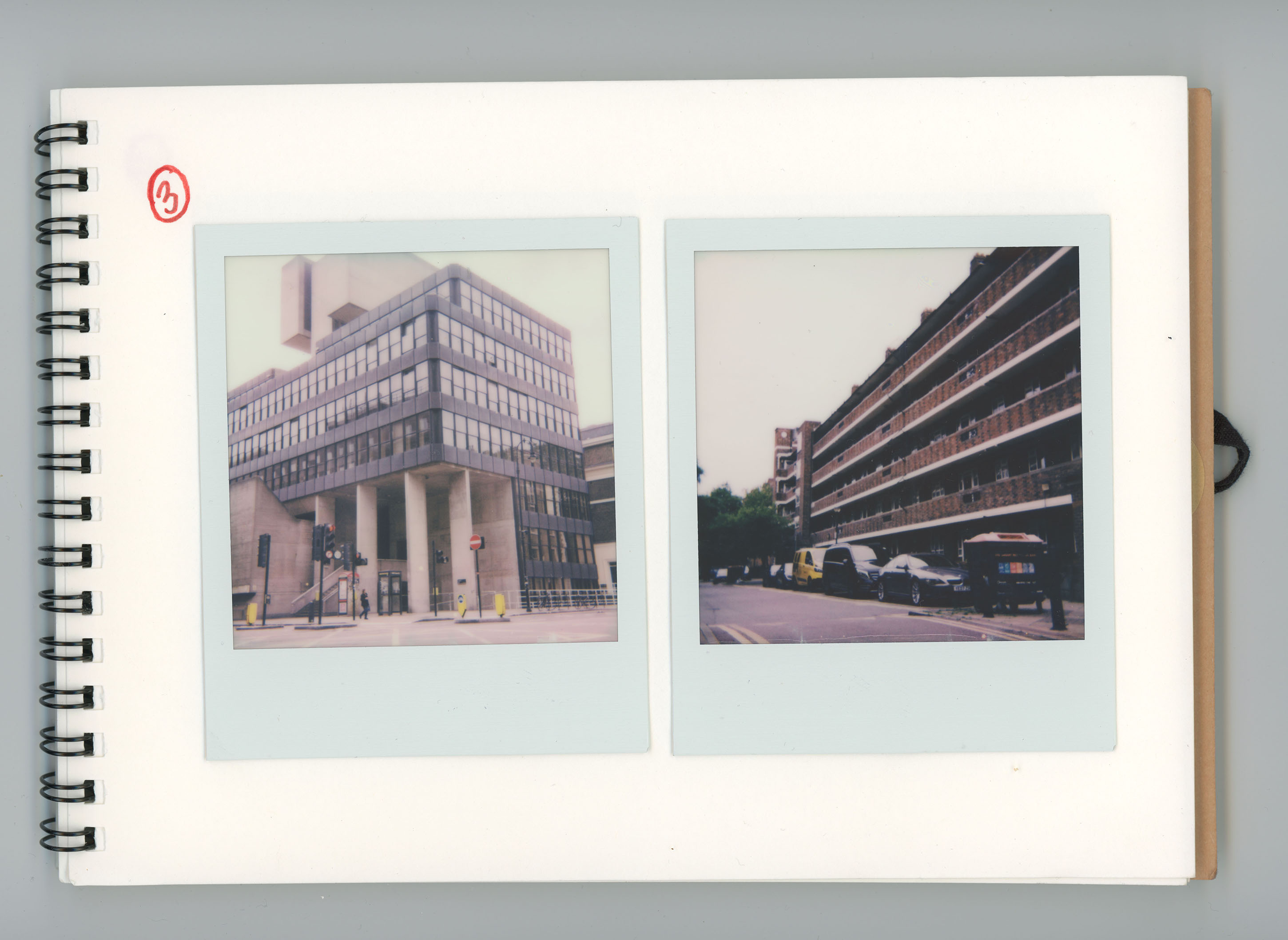

Walking through the gridded COVID-19 quietened roads of Bloomsbury, I capture a few photographs. I pause, kneel down and place a few polaroids in my bag. I try to reflect on the grandiose landscape. The residential homes, hotels, museums, libraries and universities. The lack of council estate fencing, barbed wire and no ball games signs. As pleasant as these gardens and squares are, much to my dismay I know that many of these institutions bear their own insidious legacies.

2.

The streets are clean, and the facades are imposing. Despite this locale being seemingly open to all, I know this place is not for me. Or people who may look anything like me. I know this landscape is soaked in colonial and eugenic legacies. This is true for Bloomsbury’s history and its present day. This is especially true for the university and its hostile polices. Passport checking, precarious contracting, support staff outsourcing and the draining microaggressions experienced by people deemed the ‘other’. Again people who look anything like me.

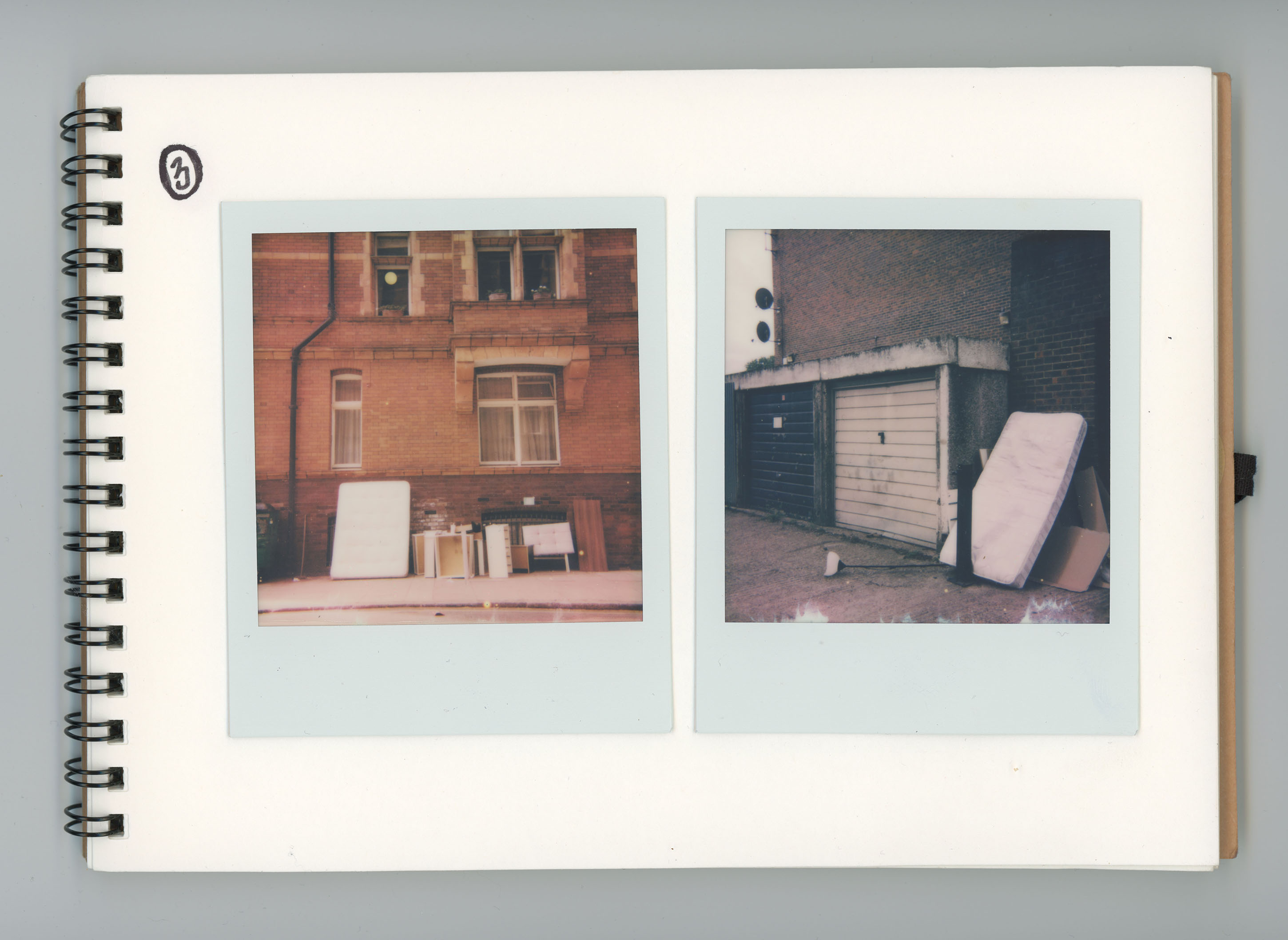

3.

As I walk through the landscape, I can’t help but notice the serene lack of crowds of student and researchers. I notice a discarded mattress amongst neatly organised debris. And I experience a brief moment of Déjà vu, taking me back to similar scenes on my estate. Ostensibly wealthy university estates, or underfunded and neglected council estates. The ubiquity of the flipped mattress reeks of aged collective ambivalence.

3.

As I walk on to university streets, I notice the hyper visible security guards in hi-vis-vests. I exchange subtle head nods unconsciously with west African aunties and uncles. Because that’s exactly what they are to me. Aunties and uncles, before being security guards. It’s in these humble fleeting moments that we share quiet understandings, amidst violent day to day work and study.

3.

At the vanguard of the IWGB movement, Uncle was at the podium with a microphone speaker. Elevated above the crowd on the steps of a university building. Amongst the crowd of supporters, students and staff, I witnessed his determined passion for his rights as he shared his frustrations, hopes and happiness in standing firm by his actions. In all honesty I was inspired. I was humbled. And I truly appreciated his speech. For here is someone who is fighting to survive the structural hostilities of work and livelihood in this grand city.

4.

Before my cycle home, I sort through the developed polaroids I photographed on Bloomsbury’s streets. I’ve made this journey from the universities, galleries and libraries to my estate and the estates of friends and family for the last six years. By train, bus and bike. Backwards and forwards. From the mostly unknown nooks and crannies of North West/ West London, to the aged lattices and bright new buildings of Bloomsbury. The juxtaposition is uncanny, and fighting against daily hostilities in both landscapes is no easy feat.

The thought alone recalls instances of heated debates and dialogues held late night on cold winter concrete balconies. Or mid-afternoon, on estate Summertime baked brick walls. Despite the visceral hostilities of my estate and others, these unforgiving landscapes are still places to call home. It is on these balconies, walkways and brick walls that I engaged with my peers and my surroundings. Listening or chiming on dialogues with other young Black men. Jumping from theme to theme. How to fight back against stereotypes. And who stabbed who last week. The outlining of ambitions and dreams. And who shot who last week. Police tape being put up and our various contemporaries prison visits/prison release dates.

These are everyday discussions centred on the hostility of the estate and the endeavours of a few young Black men. Somewhere between my journeys from estates to universities, I realise many of us strive daily to reconcile and fight against each landscape’s hostilities. Day after day we raise up to pursue our endeavours, knowing acutely what we are up against. We’ve been aware for so long, that the madness of these hostile environments becomes the accepted norm. We have some ways to go in overcoming many hostilities. However its 2020, an age of unprecedented change. I also realise that no matter what hostile environment we occupy, we are, who we are. wherever we are. And I truly believe that we take this grounded sentiment and put it to work in our actions, words and practices.

In our hopes for a new tomorrow, we must never give up fighting. We must never lose sight of the day that is yet to come. Uncle is at the podium, and I am behind the polaroid.

NATHANIEL TELEMAQUE

Author Bio

Nathaniel Telemaque is your friendly neighbourhood Visual Artist, Writer & PhD Researcher. Bearing witness to mad cities and maverick livelihoods. His lens-based works are an appreciation of the ordinary and the mundane. A montage praxis characterised by an age of unprecedented societal change. Utilising 35mm film photography and reflexive writing as a primary mediums of creative expression, He is currently engaged in a Geography (Practise-Related) PhD at University College London. As a member of the visual arts & records collective Pesolife, he collaborates and curates various distinctive projects with a variety of communities and artists.