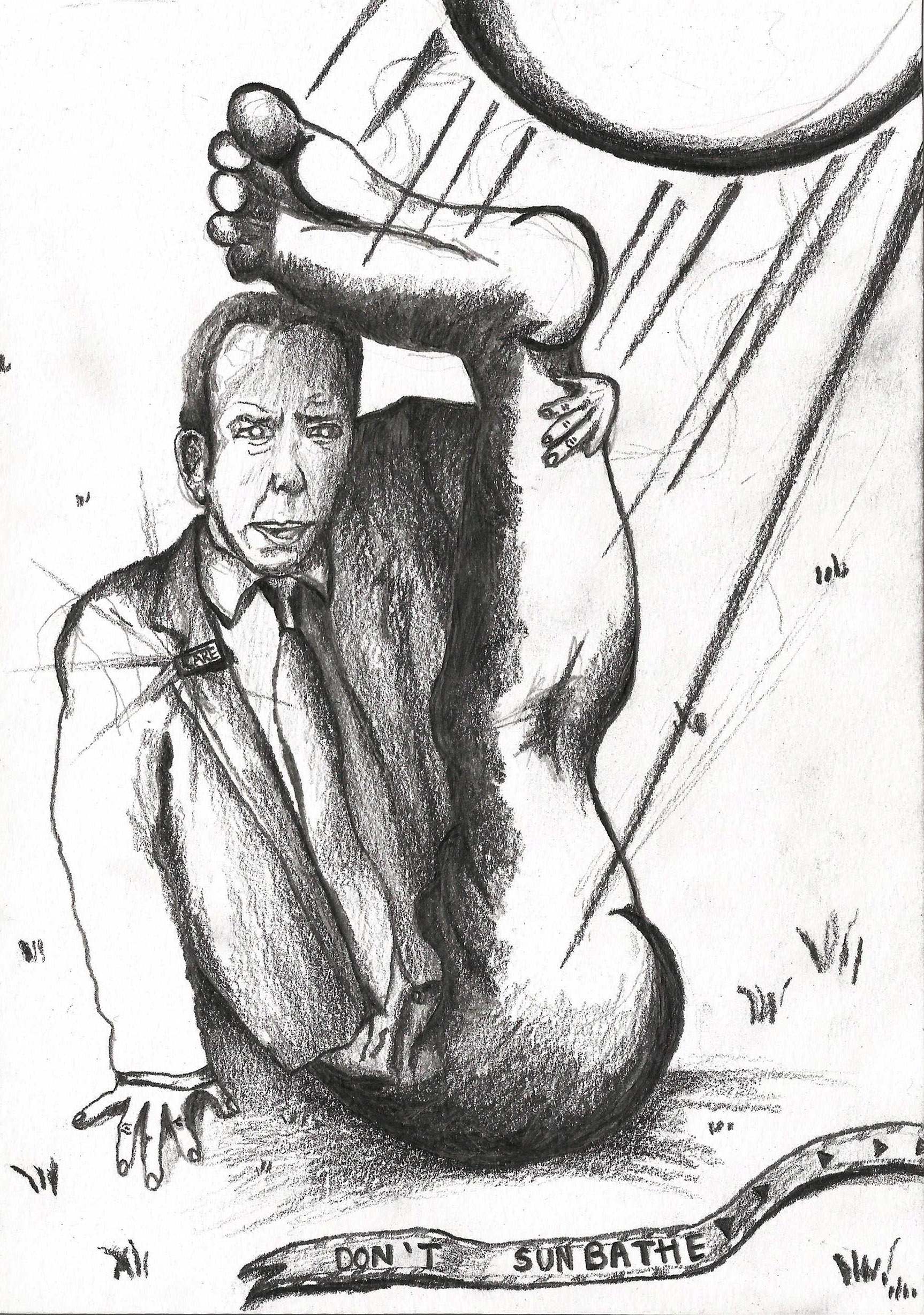

DON'T SUNBATHE

A chorus of thirty 14 year olds emerge from both stage right and stage left, with pots and pans. MONOPOD performs DON’T SUNBATHE. At the lines “Call 111”, “Call 111!” cast of 14-year olds bang pots and pans with wooden spoons, in time with one another, merging into audience applause.

“Don’t Sunbathe,” said the minister as he stood, pallid in the morning briefing sun of the spring. “For nation’s sake, don’t sunbathe.”

Under a thin breath the minister cursed the hand that had leapt forward an hour sometime in the preceding days, beckoning noon ever closer. He tightened his grip on the podium, on which the government relied for subtext, simultaneously occupying his hands so that he wouldn’t touch his face. A slither of light hit his cool forehead. He levelled his gaze at the lone lens positioned two metres in front of him; minister to citizen.

“It’s not allowed.”

He squinted up at the white blue sky and hurried back inside. The sun would soon reach its peak.

As well as sunbathing, there was an embargo on criticism: lives were at risk. But, just as certain south-effacing kitchens and westerly crooks were caught in a red evening glow, the hard consonants of “Hypocrite!” and “PPE!” spat out from the garden-less, window-less shadows where shame had been prescribed. Some people remembered how the darker inhabitants had been chased out of the nation just weeks before. Now those who were medics were allowed to stay for another year, providing nobody got any tanner.

At the dawn of “civilisation”, the roman Pliny the Elder, spoke of another race of people to the East: the Monopod, who, instead of two legs, possessed one giant foot on the end of one large leg. This deviation from the Western norm was not thought ofas a disability: in fact, Pliny noted, the Monopod possessed extremely high-levels ofdexterity, stability and resilience. One particularly impressive advantage, Pliny noted, was their ability to curl their giant foot over their regular sized bodies, in order to self-shield themselves from the hot Oriental Sun.

Much later, in the 80s, it was realised that much of the Orientalist discourse that had emerged from Western society (from the Greeks to Romans to Brits), didn’t have much to do with the realities of the East at all. Rather, mythical Eastern monsters were much more likely to tell us something about the white people who lived in the West: their imaginations, their customs and their relationships to their bodies. Tales of toe-shaded monsters abroad had been invented to highlight our own two- legged gleaming race. As it turns out, the Monopod wasn’t ‘the exotic Other’, which makes sense if you think about it. After all, those in the East were known to be a sun-tanned people. Rather, we were the Monopod all along.

Back safely in his chamber, the minister lay on the floor as the eerie blue light ofthe NHS website intermingled with the rays piercing through the sash windows, giving him an other-worldly complexion. Placing his hands across his chest, he slowly began to pull his knees towards his head, keeping his legs bent at right angles, until his buttocks and tail-bone rose off the floor, at which point he extended his legs towards the ceiling. And as he began to crunch, legs together, head bobbing up and down, lower abdomen beginning to burn; the minister fondly cast his mind back to his Classical training at Oxbridge. He remembered the Monopod; that self-shading, large-footed

product of the dexterous white imagination. And slowly but surely the minister pushed himself harder, curling and pulsing so that his head became ever closer to his feet. And the shadow he cast seemed barely human, instead: a monstrous being with a giant foot, protecting himself from high- noon sun. And, as if involuntary, in the heat of the rays as they struck the naked underside of his foot, the minister kept pushing, until his foot and his head were almost touching, until, in an astonishing feat of resilience, they connected.

With a thud, the minister collapsed sideways onto the floor, foot in mouth. Beads of sweat ran along his forehead and sole.

“Call 111,” the minister screamed to no-one through his toes, “Call 111!”

ROSA-JOHAN UDDOH

Author Bio

Rosa-Johan Uddoh is an interdisciplinary artist working towards radical self-love, inspired by black feminist practice and writing.

Through performance, ceramics and sound, she explores an infatuation with places, objects or celebrities in British popular culture, and the effects of these on self-formation. She is still influenced by her architectural background, rooting stories in specific spaces and materials.

Rosa studied Architecture BA at Cambridge University, MA Fine Art at The Slade (UCL) as a Sarabande Foundation Scholar. Recently, Rosa has exhibited at: Tate Modern, Jupiter Woods (solo), Black Tower (solo), Bluecoat, Tate Britain and published writing in The Architectural Review. She is a New Contemporaries 2018 alumnus and was the Liverpool Biennial & John Moores University Fellow 2018-2020. Rosa is currently a Lecturer at University of the Arts London and has just been awarded the Stuart Hall Library Residency for 2020.