Crossroad at the Decade of Upliftment

“If you are taught or instructed in the English language, you should be aware that the assumptions which underpins that language are your enemy.” James Baldwin

At what point does someone become a national in a nation? It’s a question which perplexes people of African descent domiciled in Western (and some Eastern) nations. This conundrum was bought into sharp relief lately by the perfect storm of crises which has enveloped global consciousness and the debate surrounding redress and progress seems to have disappeared from the front pages and headlines almost as quickly as the protests and demonstrations have subsided (in some cities). Michael Massive looks at the long term prognosis for racism during this metaphorical new age of enlightenment.

This essay unfolds as a series of portraits of inspirational figures in the struggle for Black presence and futurity in Britain, placing their histories alongside research and activism that has sought to craft spaces of possibility in the face of enclosure. Through these character studies, Massive touches on a multitude of scales and institutions and their relationships with people of African and Asian heritage; from global governance to the British state, assessing the mainstream media’s perceived encouragement and endorsement of the “school to prisons pipeline”, and also from university education to the experiences of working in academia.

When the United Nations declared 2015 – 2024 as the decade for People of African Descent, there was hope that signatories, such as the UK government would address the tag-lines offering “recognition, justice and development” as a call to arms. As expected, the UK government almost immediately followed suit with their Western counterparts and announced it “had no plans to mark” the declaration. Therefore, the UN’s avowed declaration to eliminate racism and enhance the socio-economic prospects and political representation of African people across the globe was merely met with lip service and platitudes.

The global protests in response to the assassinations of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and the regular incidences of police brutality in the US plus the coincidental revelation of the disproportionate impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on peoples of African and southern Asian descent in the UK highlighted the pervasiveness of racial inequality throughout our planet. In Britain, the spectre of state-sponsored brutality and random savagery which ebbed and flowed in the wake of countless short term right wing organisations had led to the deaths of the likes of Joy Gardener, Sean Rigg, Roger Sylvester, Cynthia Jarrett and Rashan Charles. This provided an atmosphere where resonance with the US terrordrome seemed inescapable, once sufficient numbers of people were informed that the maelstrom was actually taking place. Additionally, 2020 has witnessed a growing consensus that the negligence and sloth of successive governmental administrations were sufficient grounds for searing indictment but the revelation of the scandalous targeting of the so-called Windrush generation identifies the British establishment as beyond merely myopic to malevolent.

The simmering discontent following the revelation of the Tory government’s 2010 decision to deliberately target the offspring of the Windrush generation who had been invited to post-war Britain to re-build the economy of the victorious but war-ravaged nation. The children of the original settlers (named after the ship that delivered the first intake of Caribbean settlers to British shores) had usually arrived during the 1960s and early 1970s, completed their education and had worked here all their lives and then were victimised by an immigration policy which regarded them as “low hanging fruit” because a large percentage of them travelled to Britain on their parents’ passports. By 2012, the Home Office had totally and maliciously destroyed all the landing cards which were filled in on behalf of pre-pubescent children who had docked. Police and immigration officers embarked upon hosts of dawn raids on households of citizens who had lived their lives in Britain, but were now at odds to find the (handwritten) copies of the documents they would have received 40-50 years previously. School reports, photographs and payslips were ignored as irrelevant, if the now vital Landing Cards were unobtainable. Families were ripped apart as citizens of forty and fifty something years standing were deemed illegal residents and were stigmatized as ineligible for employment (hosts of them lost their jobs), welfare benefits and National Health Service medical treatment, social housing, pensions or even to apply to renew British passports.

Between 2012-2017, 850 people were wrongly detained, 83 people were deported and at least 13 of these unfortunates died before they could be returned after public pressure forced the Home Office, in April 2018, to acknowledge their malevolence in launching their campaign of attrition. In the aftermath, over 8000 people were given documents confirming their legitimate residency; by April 2019, the Home Office launched the so-called Windrush compensation scheme amidst much fanfare. However, to date, the complex application process means only 1275 people had submitted their claims for compensation by March this year. Only 60 of that number have actually received any payments, with the piddling sums of £4,400 being the standard norm.

The magnitude of the turnout for the George Floyd/Breonna Taylor protests throughout the UK during May and the demographic diversity of the participants indicate that the general public understand and condemn what is going on and also suggests that the Tory party which presently hosts the government mandate is woefully out of touch with the sensibilities of the nation at large.

Any claims of ignorance of the magnitude of the problem is confounded by the commissioning of a succession of expensive investigations which appear to gather dust in the libraries of Cabinet members. There exists: the Lammy review of the criminal justice system, the Race Disparity Audit, the McGregor-Smith ‘Race in the workplace’ report, the Parker review of ‘Ethnic diversity of UK boards’, the Mental Health Act Review and hosts of other independent reports highlighting the size of the gap between the UK government’s claims to preside over a “just and fair society” and the reality of the plight of working class citizens who are further impacted by their complexion and non-European heritage. The UN Working Group of Experts on People of African descent and UN Rapporteur on Racism reports also showcases the dire extent of global African socio-economic impoverishment and provides expert advice on how to redress the imbalance. However, neither the UK nor any other of the Western World’s offending hierarchies, seem willing to acknowledge that the plight of people of African heritage is directly attributable to the role of over 200 years of enslavement during the TransAtlantic slave trade and the succeeding implementations of colonialism and the ongoing neo-colonialism which continues to form the bedrock of the prevailing inequalities that continue between resource-poor/financially affluent Western nations and resource resplendent and financially impoverished African nations.

The will to dismantle neo-colonial criminality which prevents the onset of the widespread African industrialisation which would undoubtedly elevate the prospects of the continent’s nations appears totally absent from the agenda of the UN and the political elite. The ‘fourth estate’ characterisation accorded to the mainstream media perfectly evaluates how their attitudes dovetail into and reflect the societal norm. Examples illustrating the mainstream media’s conformist status and distance from the communities it purports to serve are provided on a daily basis. The BBC, for instance, regularly confuses the identity of high profile Black people – recent examples include footage of US basketballer LeBron James in a feature on the deceased fellow basketballer Kobe Bryant and the discomfiting labelling of MP Marsha de Cordova as her fellow Labour MP Dawn Butler – suggest the BBC’s claims of cultivating a diverse and representational workforce are flagrantly fraudulent. Dr Shola Mos Shobamimu, Founder of the Women In Leadership forum describes the corporation’s repeated failure to attain 21st Century standards as “institutionally dysfunctional”.

Dr Shobamimu was herself marginalised in the mainstream press when her attendance in support of broadcaster Samira Ahmed in her successful challenge to the BBC’s discriminatory pay structure saw her labelled simply as “a friend”. “Clearly, there is no threshold of shame for the BBC,” stated Dr Shobamimu. “The BBC keeps demonstrating an ineptitude worthy of an institutionally dysfunctional organisation projecting bias and feeding negative stereotypes,” she added.

Many have identified education as the arena where the acceptance of inevitable change is most discernible albeit slow. The relative shortfall of access and the plethora of obstacles which confront students of African and Asian descent has not halted the upsurge of Asian and African academics who resist a de facto brain drain to Western countries, choosing instead to return the lands of their birth or family heritage, seeking to contribute their precious skills to their home nations.

This is by no means an attempt to underestimate the difficulties which confront students, members of faculty and activists who presently attempt to negotiate traction through the scholastic minefield. The road has been and continues as a hard knock travail but many believe there is greater light at the end of the Western world’s dismal scholastic tunnel than within the corporate and political platforms. The struggle against marginalisation and disenfranchisement in education starts early in Black families. Indeed, almost from day one, the phenomenon identified as the schools to prison pipeline commences with young Black males seemingly earmarked as potential troublemakers who the system warns teachers to be particularly draconian with in their dealings.

These attitudes were first chronicled by Grenadian-born activist Bernard Coard in his seminal 1971 work How the Westindian Child Is Made Educationally Sub-Normal in the British School System. Coard’s analysis collated the activism of groups such as the Caribbean Education and Community Workers Association, the Bogle L’Ouverture and New Beacon Movement, the West Indian Standing Conference, the Black Education Movement and the Black Parents Movement and their successive battles against the disproportionate sectioning of Black boys in Educationally Sub Normal (ESN) institutes. However, although their pugnacity eventually forced the British education system to admit it had mishandled at least two generations of Caribbean heritage children, the response from the authorities came by way of claiming contrition but effectively replacing ESNs, with Special Education Needs (SENs), and the even more ominously titled Pupil Referral Units (PRU). Many identify PRUs as the first level of the continuation of Western society’s fear of and obsession with identifying and suppressing the mythical ‘Black messiah’, which commenced with the first ships transporting kidnapped Africans from their homes to the ‘New World’ on through to Dutty Boukman, Harriet Tubman, Toussaint L’Ouverture, Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, Claudia Jones, Martin Luther King, Angela Davis, Maurice Bishop, the Black Panthers, Esther Stanford-Xosei, Walter Rodney, Assata Shakur, Thomas Sankara and beyond.

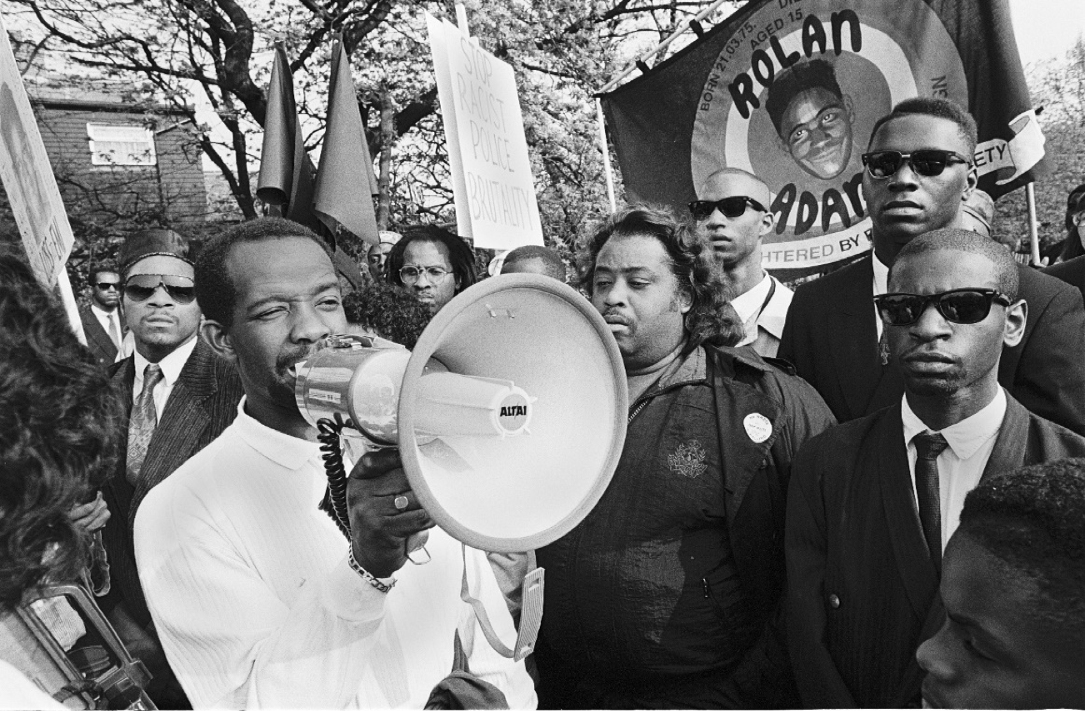

Gus John, an Associate Professor of Education and Honorary Fellow of the London Centre for Leadership in Learning at UCL’s Institute of Education, has made several notable interventions in Britain’s race relations during his long and distinguished career as a community activist since his arrival from Grenada as a theology student. Professor John’s co-founding role of the first Saturday/Supplementary school in Handsworth, Birmingham in 1968 kick-started his lifelong participation in “schooling and education, youth development and the empowerment of marginalised groups within communities”. Professor John’s experiences in youth development in Handsworth and later Moss Side, Manchester, formed the basis of the 1972 tome Because They’re Black, his collaboration with Derek Humphry, which was awarded the Martin Luther King Memorial Prize. The continuity which saw the 1976 publication of The New Black Presence in Britain and Professor John’s enlistment to Lord David Pitt’s Campaign Against Racial Discrimination segued into his participation in the response to the tragic 1981 New Cross Fire, where 13 Black teenagers lost their lives following a suspected arson attack on January 18.

There was a perceived absence of sympathy from the UK establishment, including antagonistic reports in the media, no messages of condolences to the families of the children from any members of the Royal Family nor any Church of England clergy. In addition, the police investigation showed gross ineptitude and rumours identifying the presence of “unknown persons” shortly before the blaze, have never been substantiated. However, the very nature of a life experience which embraces an understanding that the late ‘70s era New Cross’ south-east London locale’s repute as a notorious hotbed of racially motivated violence, made the awful possibility of a random act of malice entirely probable. The seemingly curt dismissal of these claims by the police and the bull-headed pursuit of further unsubstantiated lines of inquiry into alleged culpability of some of the victims led to outrage. The exacerbating communication breakdown further alienated members of Britain’s nationwide Black community who already believed themselves to be outsiders in the society they lived and worked in.

Amongst hosts of others who saw the tragedy as a watershed in the Black community’s relationship with Britain’s mainstream society, Professor John joined the New Cross Massacre Action Committee, launched a chapter in Manchester and became an organiser of the Black People’s Day of Action in London on March 2 1981. Seething tensions exacerbated by the police’s failure to file charges against anyone for the New Cross Massacre led to subsequent nationwide protests following the Black Peoples’ Day of Action which escalated into uprisings following the militaristic response of riot gear-clad police in the heartlands of London, Birmingham, Bristol, Manchester, Leeds, Sheffield, Cardiff and Liverpool. Professor John chaired the Moss Side Defence Committee in Manchester and acted as adviser to the Liverpool 8 Defence Committee in Toxteth. Further distinguished service as the co-ordinator of Manchester’s Black Parents Movement, his role in establishing the innovative Education for Liberation book service which evolved into the International Book Fair of Radical Black and Third World Books in Manchester, London and Bradford led many observers to claim that Professor John epitomised the template for the perennial scholar activist. As a member of the 1987 Macdonald Inquiry into Racism and Racist Violence in Manchester Schools, following the 1986 racially motivated murder of 13-year-old Ahmed Iqbal Ullah, Professor John co-authored Murder In The Playground: The Burnage Report with Ian Macdonald, Reena Bhavnani and Lily Khan.

Following the foundation of the George Padmore Institute, where he acted as trustee alongside chairman John La Rose, Professor John became the first Black person in Britain to be appointed as the head of a local authority’s department when he became Director of Education in Hackney in 1989. The amalgamation of two departments saw Professor John become Hackney’s first Director of Education & Leisure Services, a post he held until 1996. The seemingly indefatigable Professor John has virtually internationalised his consultancy work and is a contributor to an exhaustive number of educational initiatives. He continues mentoring scholars and advising forums in Britain and also advises member states in Africa and the Caribbean (Cameroon, Jamaica, Somaliland, Lagos State). Professor John’s passion and expertise has been duly recognised by the African Union since 2006, when he was appointed in his ongoing role as a member of the Union’s Technical Committee of Experts working on “modalities for reunifying Africa and its global diaspora”. In Britain, his legacy and example has been a cornerstone for those who have taken up his mantle of champion for the people.

Cometh the hour, cometh the (wo)man. One of several redoubtable adversaries of PRU’s schools to prison pipeline paradigm is social enterprise entrepreneur Cheryl Phoenix, the founder of The Black Child Agenda (BCA). The BCA assess that Black and mixed heritage students are 167 times more likely to be assessed as SEN and referred to PRU, with attendant suppressive procedures such as sanctions, fixed term and permanent off site exclusions for perceived infractions, such as wearing non-chemically treated hair or questioning teachers on their delivery of a reductive curriculum which obscures the role of African people in world history and offers a revisionist tract on global accomplishments such as the abolition of the TransAtlantic slave trade and the defeat of Nazism and fascism. The BCA have also challenged the discrimination faced by children and families with physical disabilities and mental health issues and also families impacted by bullying. To date, the BCA have never failed in any intervention they have made on behalf of visible minority or disabled students. Some observers have identified this ongoing war of attrition as an attempt to prolong the policy of keeping kidnapped Africans under-educated and ill-informed, a key component of maintaining rule on slave plantations.

For students of African and Asian heritage in higher education, the minefields are myriad but depressingly familiar. Overseas students provide a seamless source of valuable revenue for Britain’s higher education institutes and universities, for although they speak highly of the quality of tuition they receive and of the commitment of members of faculty and administrations but many express misgivings concerning the level of support they receive from outside agencies.

Within the higher echelons of academia, great ingenuity is being exercised to offset centuries old attitudes which continue to erect obstacles to long term progress. Traditionally, universities have not been kind to non-European academics but there appears to be a greater appreciation of the value that diversity adds to the system. For instance, for metaphorical eons the University College London (UCL) has celebrated arch eugenicist Francis Galton, despite his centrality in a discredited field of study many believe existed purely to justify the Maangamizi (TransAtlantic Traffic of Kidnapped Africans) and the colonialism which ensued. Galton’s bestowal of his collection of materials and writings to UCL had seemed like a poisoned chalice when student activists challenged the institute during the “Why is my curriculum white?” campaign. The UCL sought to handle Galton’s troubled legacy with the appointment of the gifted Subhadra Das as the lead curator. Das approached Galton’s unabashed bigotry with justifiable disdain, but handled the delicate materials he had bequeathed her institution with due care and impeccable professionalism. UCL has further attempted to pre-empt the zeitgeist in the aftermath of the slave-master statues controversy by renaming three buildings (including two lecture halls) which formerly regaled Galton and fellow xenophobe Karl Pearson. It must, however, be noted that the final re-naming only took place in June, at the height of the George Floyd/Breonna Taylor protests and following the spectacular toppling of slave trader Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol, a full six years after Professor Joe Cain implored the UCL to remove Galton’s name from the lecture theatre.

William Lez Henry, Professor of Criminology and Sociology in the School of Human & Social Sciences at University of West Lez London is only too aware of the contradictions inherent in Western education from kindergarten to university for academics of African descent. Born in South London to Jamaican parents, he describes himself as “an African born in the womb of a scornful mother” but advocates education as a necessary tool for the eventual dismantlement of racism and the total liberation of the African continent. “Universities deliver exactly what they promise to,” he told a recent African Liberation Day commemoration forum entitled Diasporan Challenges In Academia. “Your degree is a tool which you need to use to your best advantage,” he added.

Professor Henry may be an unlikely poster child for an academic prototype, but his journey demonstrates that there are alternative paths for traversing the academic minefield. He was expelled from school at 15, for fighting, and permanently excluded from a further education facility one year later, for fighting. Nevertheless, Prof Henry qualified as a plumber and heating engineer and became a certified Industrial Pipe Fitter. His Lezlee Lyrics alter ego saw him become a recording artist with a reputation for taking on all-comers during sound system MC ‘battles’ (with lyrics, not fists) throughout UK reggae’s early 1980s golden age.

In 1993, the Black community was, once again, conflicted. The mainstream indifference to the racially motivated assassinations of Stephen Lawrence on April 22 and 15-year-old Rolan Adams in 1991 left many questioning the British establishment’s commitment to the wellbeing of its Black and visible minority population. Both youngsters were murdered during the achingly innocuous act of waiting at bus stops for transport home as chilling postscripts to the 1959 massacre of Kelso Cochrane. Although Rolan’s death was met with a ten year sentence for 19-year-old gang member Mark Thornburrow, the indifference displayed by the mainstream society seemed callous. The Damascene change of attitude which saw right wing tabloids and broadcast corporations hypocritically calling for change they previously denied was necessary was actually precipitated by the 1994 state visit of South African post-apartheid President Nelson Mandela. President Mandela’s championing of the Lawrence family’s campaign embarrassed the mainstream, particularly when he identified the unwarranted surveillance of the family by antagonistic Metropolitan police officers and the silent mainstream press as mirror images of the excesses of his own nation’s apartheid era. Although the furore would eventually lead to the commissioning of initiatives such as the McDonald Inquiry which characterised bodies such as the Metropolitan police as “institutionally racist” and lead British society to review its approach to developing a more inclusive and evolved sense of fellowship, in 1993 the status quo was unapologetic and recalcitrant.

Lez Henry channelled his frustration at these simmering anxieties, in addition to his discomfort at the still unsolved New Cross Fire, which took place within one mile of his family’s home, into a fresh challenge. Inspired by the tireless activism of Gus John, Henry enrolled at Goldsmith’s as a mature student. He took on several research and lecturing roles over a seven year tenure following his graduation and also achieved his doctorate. On leaving Goldsmith’s in 2002, he founded his Nu Beyond initiative as a fulcrum for multi-faceted corporate endeavours, which included the publication of his three books.

Professor Henry’s return to academia in 2014 saw him determined to chip away at the discrimination and marginalisation which stymies the efforts of literally hundreds of non-white academics. Out of the 18,000 holders of Professorial chairs in the UK only 130 are of African heritage. Most academics of African heritage are employed on short term renewable contracts as fractionals, teaching academics or research academics. Determined to smash through this scholastic glass ceiling, Henry worked his way up from part-time and hourly paid contracts, throwing himself into what he claimed was a vigorous bout of “upskilling”.

“I sought to demonstrate my value to the institution by identifying weaknesses within the institution,” he stated. “I demonstrate how I satisfied Professorial criteria by highlighting my attributes beyond lecturing,” he continued. “I participated in extra curricula forums which emphasised my public profile, my research profile, my high community profile and I wrote them up,” he added. “As well as peer reviews there were various periodicals and even my self-published endeavours. When I first self-published in 2006 it was almost unheard of but it was necessary for me to claim agency over my work. Baldwin once said we are educated away from ourselves because although our methodology, literature review and fieldwork are conventional, the content and conclusions we come to may be alien to the people judging its merit.”

Henry accepted the Professorial chair last year and conducts MA and PhD supervision as well as hosting a Pathway to Personal Success programme, in addition to teaching Five Animal Style Kung Fu. And it don’t stop. Professor Henry hosts a groundbreaking youtube interview series, entitled Outerview and has addressed what he describes as the “intentional homogeneity” of academia by demanding a presence on interview panels to assist the effort to achieve parity throughout the faculty.

Although the United Nations might have declared the 2015 -2024 era as the Decade of the African Descendant, there is little indication that the United Nations nor the Western governments which subscribe to the letter of the edict have the slightest intention of making 2024 any different to 1784 (before the Haitian Revolution). The portraits and histories outlined in this feature, articulates some of the many courageous acts which should inspire us, the African descendant to continue moulding this decade into the watershed we require for her/him/ourselves; from holding the media to account to creating and fortifying our own platforms, critiquing existing educational systems and striving to create new sites and spaces of learning, we must and will persevere. It don’t stop and we won’t either.

MICHAEL MASSIVE

Author Bio

Michael Mattus (aka Mikey Massive) is a wordsmith who utilises semiotics in essays, sonnets and literature to inform, illustrate and communicate perspectives and outlooks which he hopes may lead to debate concerning an alternative viewpoint to the prevalent template which many believe sets the world's peoples against their inherent humanity. Crossroad at the Decade of Upliftment is a collaboration with renowned news/action photojournalist Rod Leon (rod@all_images) which discusses whether the latest groundswell of discussion concerning societal diversity will lead to long-term systemic progress, or whether it is merely another hiccup jerk response to individual acts of injustice.